When we first began planning our itinerary for this big adventure, we knew we wanted to dedicate some time towards a volunteer opportunity or philanthropic venture. It was, in fact, the first part of our trip that we booked, and it became an anchor to build the rest of our travels around. Our intent was to bring some balance to this highly indulgent experience, shift the focus away from ourselves, and hopefully do something good for the world.

Lindsay had previously participated in a volunteer travel expedition through a company called Earthwatch, and had a really positive experience; it was a simple decision to utilize the same organization for our purposes. We quickly narrowed our focus to wildlife and environmental conservation as a common interest, and then reviewed the options that aligned with our timeframe and general travel destinations. We ultimately chose a project called Conserving Endangered Rhinos in South Africa. The briefing memo we received included this description:

“The current extent of poaching and consequential declines in rhino population throughout Africa is shocking. On average more than 3 rhinos are illegally killed every day in Africa and at the current rate this species may go extinct in the next 10-20 years. Our project aims to help conserve rhino populations by providing evidence of the impacts of different management on the behavior of rhinos and investigating how they are essential to support other biodiversity. As part of this Earthwatch team, you will be involved in monitoring the rhino movements and recording their behavior as well as assessing bird, mammal and invertebrate biodiversity associated with rhinos and their habitats, helping to collect evidence to protect and value these animals for the future.”

On October 10th we met our fellow team members at the rendezvous point in the Johannesburg airport, and set off on the 2 hour drive to the game reserve that would be our home for the next 12 days. Situated very near Pilansberg National Park in northwestern South Africa, Mankwe is a private game reserve run by the MacTavish family and their trusted, talented team – people with a long history and deep passion for the African bush. We were warmly welcomed by the team, including the project Principal Investigators – Lynne, Niall and Sam – the staff, and Nkombi volunteers (mostly university students with special skills related to conservation). We quickly settled into our new digs – a humble yet comfortable safari tent that we shared with a few other critters – and joined our fellow team members to explore the camp.

Mankwe game reserve is a 4,750 hectare wildlife oasis in the middle of human civilization. Power lines are visible along the horizon, and at night, we could occasionally hear music drifting in from the nearby township; trash blown into the reserve was another unfortunate sign of the proximity of people. From the moment we arrived, we started to get a better understanding of the complexities implied by the term “human-wildlife conflict”.

The morning of our first day on the job, feeling eager, optimistic and completely unsuspecting of the emotional roller coaster we were in for, we filed into the “school room” for an introduction to the project and the work we would be doing. Lynne MacTavish, the site Principal Investigator, reviewed the project objectives and some background information:

Project Aims:

- Raise global and local awareness of conservation issues

- Provide scientific data to inform management and conservation decisions

- Increase surveillance of rhinos and deter poachers

Rhino populations are in crisis due to the high value of rhino horn combined with widespread poaching. There has been an exponential increase in poaching both white and black rhino in South Africa over the last 15 years – and South Africa is where 74% of the world’s remaining population of rhino is found, 33% of which live on privately owned game reserves. One of the eye-opening realities that we learned is that in South Africa, you can buy rhino at auction (or elephants, or giraffe, or zebra, or nearly any “safari” animal species) just like you would buy cattle in the US. The notion that Africa is a vast, wild landscape teeming with exotic wildlife roaming free, is something of an illusion, at least in South Africa. As Dougal (Mankwe’s Chief Warden) said, “As soon as you put a fence around it, you have to manage it.” Even the national parks – designated, protected lands for wildlife – there is still human intervention, such as an artificial “lake” created by a dam or the paved roads that run through the parks. Consequently, private game reserves in South Africa are literally on the front lines of rhino conservation and the fight against poaching. Those that own rhinos (as strange as it is to accept that you can own a rhino), love and care for the safety and well being of these animals.

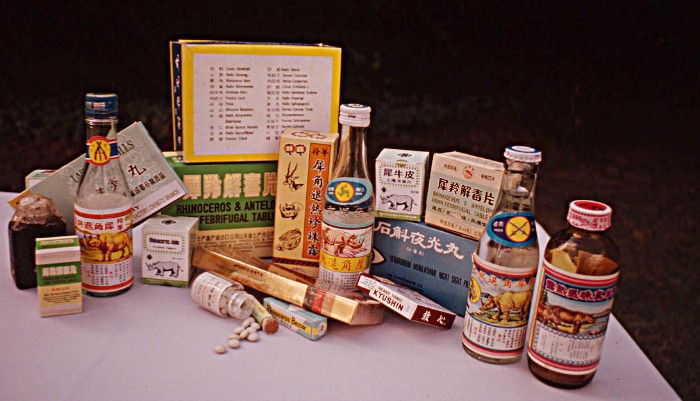

Poaching is predominantly driven by the illegal trade of rhino horn in Southeast Asia. On the black markets of Southeast Asia, rhino horn is worth more than gold; it is literally the most valuable commodity, per gram, in the world. We knew that the primary market for rhino horn was Asia, but we were shocked to see photos of packaged and branded “products” containing rhino horn; we’d always had the impression that it was an illicit trade, handled secretly through furtive transactions. But this gives it an air of legitimacy, and speaks to how entrenched and accepted it is in these markets. Even if conservationists and activists are successful in convincing 99% of people to stop buying rhino horn products, the remaining 1% would still drive them to extinction in 10-20 years.

And then Lynne began to tell us the story of the project origins. Mankwe has a long history with Earthwatch, sponsoring a wide variety of scientific research, nurturing relationships with multiple universities, hosting PhD students, and publishing scientific papers. The particular project we joined has been in existence for just about a year, having been fast-tracked in response to a tragic incident that changed Mankwe forever. Being in such close proximity to the townships and a large human population, Mankwe has always dealt with the threat of poaching – in fact, it’s a well known secret that a particular stall in the local market sells bushmeat poached primarily from Mankwe. But they had somehow managed to escape the killing of their rhino. That is, until November 2014, when they discovered one of their female rhinos killed by poachers. It was particularly brutal and cruel; a post-mortem analysis showed that the animal’s spinal cord had been severed to prevent her fighting back, and her horns hacked off while still alive, completely destroying her face. A second animal – this one a pregnant female named Winnie – was discovered later; she had died slowly of internal bleeding from a poacher’s gunshot. It was a picture of Lynne, head in hands, in front of Winnie’s body that quickly went viral, an emblem of the rhinos’ plight and the fight against poaching.

Police response was shameful. Because rhinos are classified as endangered, the illegal killing of one is considered a high crime. The Mankwe team had appropriately treated the site of the butchered rhino as a crime scene, careful not to disturb any evidence. The local police completely disrespected any protocols, trampling the area, laughing and making offensive jokes: “where’s the cooking fire? This is good meat!” When the second animal was found, the police showed up drunk, empty bottles rattling around their trucks.

The act of retelling this story was clearly taking a toll on Lynne; many of us volunteers were teary as well. Outrage, despair and helplessness. The authorities who are supposed to be defenders of wildlife are ambivalent at best, and at worst, suspected of colluding with the poachers. The fight to protect these rhino is being fought on so many fronts – it feels hopeless.

At this point, Mankwe was faced with a terribly difficult decision on how to protect their remaining animals: sell them to another game reserve (where their fate would remain precarious), or de-horn the animals? This brave team ultimately chose to de-horn their animals. Brave, because as soon as the animals are de-horned, the threat transfers to them; it is much easier for a poacher to hold a gun to them and demand they open a safe, than to risk a hunt and harvest. The process of de-horning is far from simple, and extraordinarily expensive. They first have to seek approval from the government agency Nature Conservation; this can take up to a week, during which time, the rhinos remain at heightened risk now that the poachers know of their existence on the reserve. Mankwe set up 24-hour patrols in 2km intervals along their 30 km fence line. Once the approvals came through, additional security was hired for the actual de-horning event. Eleven animals were de-horned in a last-resort effort to keep them alive. And then they faced the challenge of what to do with harvested horn itself. They are not allowed to destroy the horn – it must be accounted for to the authorities to ensure that it isn’t sold on the black market. No local bank would take it because of the high risk of violent theft. A bank in Johannesburg was located that would store it in a vault at a premium price. In a highly publicized event to make it very clear that none remained at Mankwe, all the rhino horn was airlifted by helicopter to Johannesburg for safekeeping. This is repeated every 18 months as the horn regrows.

Since then, Mankwe continues to invest heavily in anti-poaching activities to protect the animals, some through dedicated volunteers but mostly at great cost to them personally. But they do it because they love the animals fiercely, they feel a moral responsibility to the animals in their care on the reserve, and are committed to the survival of the species.

So, then we came to the hard conversation about a solution to this problem. It’s been ingrained in us that best course of action is to pursue awareness and education campaigns that counteract the incorrect belief that rhino horn has medicinal power, and hold fast on the illegal trade of rhino horn and prosecute poachers as harshly as the law allows. We arrived in South Africa confident that this was the only option, the correct way to move forward.

The team at Mankwe, along with nearly everyone else in the rhino conservation community in South Africa, is strongly in favor of legalizing rhino horn trade. By creating a regulated trade, with registered sellers and buyers, we will effectively enable the rhino to save their own species. Interestingly, the biggest surge in rhino poaching was between 2008 and 2009 – which coincides with the timing of when rhino horn trade was made illegal domestically within South Africa. Meaning, banning it had the opposite of the intended effect on the animals’ welfare. The presumption is that a legal domestic trade in rhino horn enabled “leakage” to satisfy illegal demand from overseas. Since then, poaching numbers continue to climb.

South African delegates to the most recent meeting of CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora) brought a proposal for a legalized international trade in rhino horn; predictably, it was voted down. South Africans close to this conservation issue are understandably frustrated. From their perspective, given that the majority of rhino are found in South Africa, they believe their voice in this debate should be given more consideration. It is infuriating to them that the countries that voted down the proposal contain ZERO rhino, and yet, their votes are counted equally.

We walked out feeling stunned and shell-shocked. Neither of us could remember the last time our position on an emotionally charged, highly controversial issue had been reversed so dramatically in such a short period of time. Maybe never. The more we thought about it and reflected on what we had learned, the more strongly we believed the proposal has merit. Why doesn’t the world listen more, and give more credence to the views, insights and wisdom of the people closest to this fight? How can we presume to have more expertise on this issue? When has banning something with a deeply established demand (alcohol, marijuana, prostitution, etc.) ever been successful? How realistic is it to think we could possibly change cultural beliefs older than Christianity? Certainly not within the timeframe we have before these animals are obliterated.

The cynics who say that private game reserve owners are just greedy – we can attest, as former cynics ourselves, this isn’t the case. How can you reconcile that view with the example of Mankwe – a team of people who are patrolling parameters at 3:00am, putting themselves in the line of fire of poachers, spending thousands of dollars, personally financing the protection of an endangered species. And they are one of many. In this context, the picture shifts from money-hungry villain, to one of a desperate guardian seeking legitimate resources in an ongoing battle for wildlife conservation. We had no idea of the massive expenditures associated with conservation, a burden that is too often shouldered by the private citizen.

If science can prove that rhinos are not adversely affected by being de-horned, then it seems like a solution that warrants serious consideration.

Our eyes were opened in so many ways… so much to think about.